Capacity Planning: Forecast Demand, Avoid Overload, and Hit Dates

23 Oct 2025

Software Development

Introduction

Imagine committing to a project deadline, only to realize later that your team simply doesn’t have the bandwidth to get it all done. It’s a common cause of late projects and unhappy teams. In fact, resource and capacity issues are a top challenge in project management – in a recent survey, two-thirds of organizations said balancing capacity against demand is one of their biggest resource management struggles. A related guide is Resource Scheduling 101: Time- vs. Resource-Constrained, which covers balancing tasks with team capacity and 0% (none!) rated their capacity forecasting as “very accurate”. Clearly, we need to get better at this. That’s where capacity planning comes in.

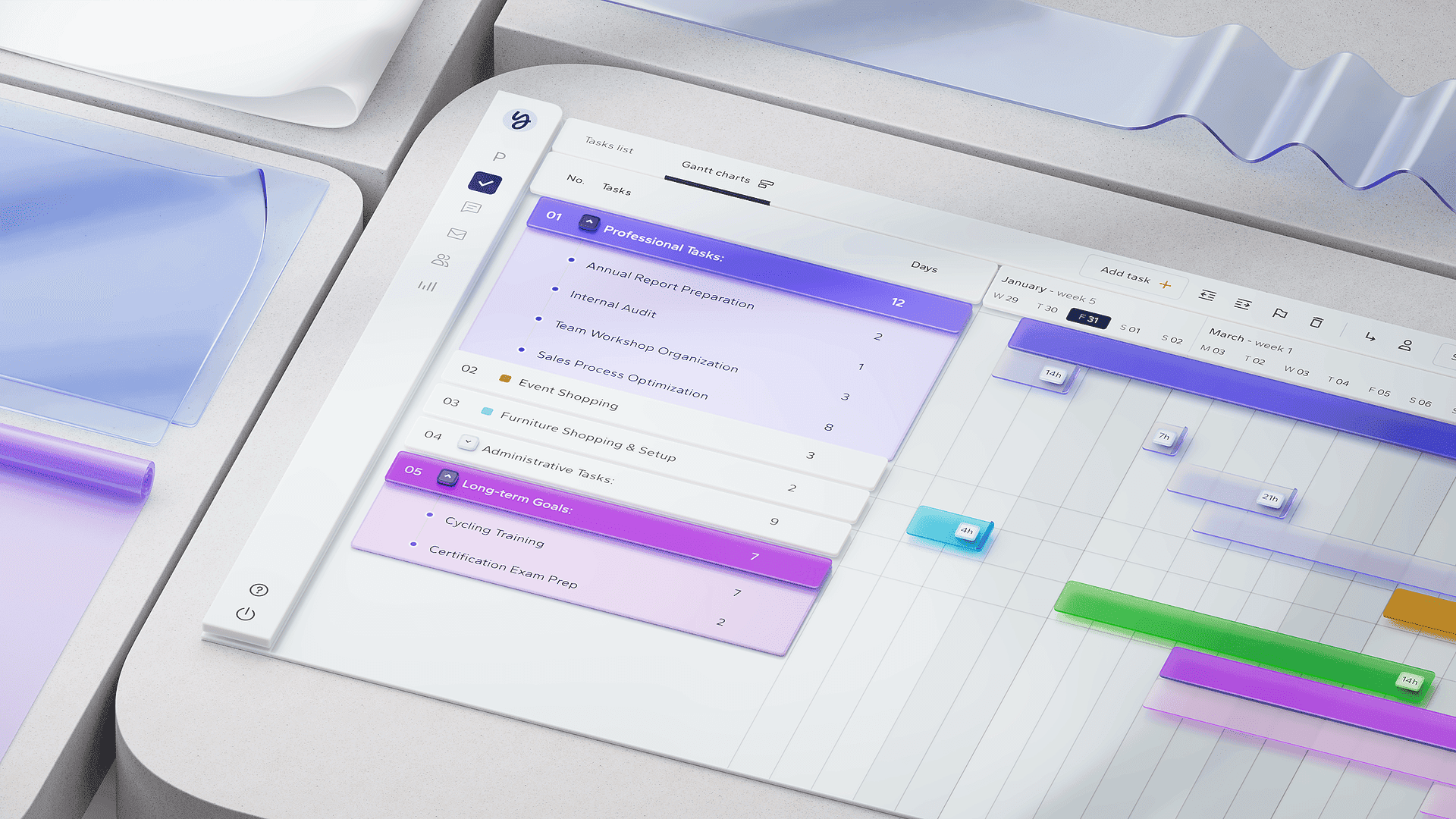

Capacity planning is the practice of determining how much work you can realistically take on with the resources (people, equipment, etc.) you have. It’s about ensuring your team’s workload is feasible so that deadlines can be met without overwork. Think of it as the bridge between lofty project plans and the reality of limited time and human energy. Even the best schedule (whether it’s a Gantt chart vs. timeline vs. roadmap: When to Use Each or sprint plan) can fail if it wasn’t grounded in capacity planning – you’ll end up with overwhelmed team members, tasks slipping, and possibly project failure. On the flip side, good capacity planning can actually improve delivery performance. According to a McKinsey report, organizations that prioritize effective capacity (workforce) planning can reduce productivity losses by up to 20-30%, potentially preventing a 10-15% loss in annual revenue that would result from overstretching or understaffing.

In this guide, we’ll walk through what capacity planning is and why it’s essential to hitting project dates, then dive into a step-by-step approach. We’ll illustrate with examples, including a simple model for a software team. We’ll also discuss how to monitor and adjust plans, since capacity isn’t static. And we’ll answer common questions, like what’s a “safe” utilization rate to target and how often to re-forecast. Plus, we’ve included a free capacity planning template (spreadsheet calculator) you can use to plug in your data and immediately see if you’re over or under capacity. By the end, you’ll be equipped to forecast your team’s workload with confidence, avoid overload, and keep your projects on track. In other words, you’ll have a safety net under your schedule. Let’s dive in.

What Is Capacity Planning?

At its core, capacity planning is the process of figuring out how much work you can handle with the resources you have, and making decisions if there’s a mismatch. In project terms, it means ensuring your team’s available hours (capacity) can meet the project tasks and timelines (demand) without exceeding reasonable workload limits. A formal definition: “Capacity planning is the process of determining the resource needs of your project. By analyzing project needs, the goal of capacity planning is to match workload based on team availability to complete projects on time.”. Essentially, it’s about balancing supply vs. demand:

- Demand: The amount of work that needs to be done. This comes from project plans, task estimates, incoming service requests, etc. Demand can be measured in hours, story points, or any unit of effort.

- Capacity: The amount of work your team can do in a given time period. This is typically measured in available hours or FTE (full-time equivalent) units, adjusted for things like holidays, non-project duties, or a target utilization (we’ll discuss utilization soon).

The output of capacity planning is usually a forecast: for example, a projection that “Next quarter, we expect 3,200 hours of engineering work (demand), and we have 4 engineers * 40 hrs/week * 12 weeks = 1,920 hours of engineering capacity. We have a shortfall of ~1,280 hours, which is roughly 2 additional engineers needed, or we must reduce scope or extend the timeline.” Armed with this insight, you can then make decisions (hire contractors, say no to some projects, push a deadline, etc.) before it’s too late. It’s much better to address a capacity gap at the planning stage than to discover it a week before the deadline.

Let’s break down a few key concepts in capacity planning:

- Utilization Rate: This is the percentage of time people are working on productive project tasks versus total time available. You rarely want 100% utilization (that would mean no breaks, no learning, no buffer). Research suggests an optimal capacity utilization is around 80% – this provides high productivity while leaving room for downtime, unexpected tasks, and rest. In fact, some experts say even 70% is a healthy target to avoid overload. In capacity planning, you often decide on a target utilization (e.g., we plan our team at 80% load, leaving 20% for meetings, admin, illness, etc.).

- Effective capacity: If one person theoretically has 40 hours/week, their effective capacity at 80% utilization is 32 hours/week for project work. Multiply that by the number of people and time period, you get team capacity.

- Timeframe: Capacity planning can be done for different time horizons. Long-term (strategic capacity planning) might look at quarterly or annual capacity to inform hiring or big commitments. Short-term (tactical) might look at the next 2-4 weeks or a sprint, to allocate tasks appropriately. Often, you’ll do a broad plan for the year and then refine as each quarter or month approaches, because demand gets clearer over time.

- Resource types: While we often talk about people capacity (hours of human work), capacity planning could also involve other resources like machines, rooms, budget (financial capacity), etc. In this article we focus on team member capacity, but the same principles apply: e.g., if a piece of equipment can only process X units per day, that’s its capacity, ensure demand doesn’t exceed that consistently.

- Over-utilization vs Under-utilization: Both are problems. Over-utilization = burnout, errors, and missed deadlines. Under-utilization = idle time, wasted potential (and possibly people getting bored or your project taking longer than it could). Capacity planning strives for the sweet spot – busy but sustainable. For perspective, a report found that chronic overutilization (over 100% allocation) leads to decreased productivity and higher turnover (burnout impacts), while underutilization can hurt morale and ROI. So, planning for ~80% avoids both extremes.

In summary, capacity planning is all about grounding your project schedule in reality. It asks: “Given our team size and other commitments, can we actually do all this by the deadline? If not, what has to change – do we get more people, reduce scope, or adjust timeline?” It turns guessing into data-driven forecasting. And it’s not a one-time thing; it’s a continuous discipline throughout the project lifecycle. Next, let’s look at what data you need to do capacity planning effectively.

Key Inputs and Data for Capacity Planning

To do capacity planning, you’ll need to gather a few important inputs. It’s like filling in both sides of an equation (demand vs capacity):

- Workload Demand: First, estimate the amount of work required for the period you’re planning. This could be:

- Project tasks and estimates: If you have a work breakdown structure or user stories with story points, translate those into effort hours or days. For example, Project X might have 500 hours of dev work, 100 hours of design, 50 hours of QA, etc. (We often categorize by skill or role, because capacity for each role is considered separately – e.g., design capacity vs dev capacity).

- Incoming operational work: If your team also handles BAU (business-as-usual) or support tasks, forecast those too. For instance, a DevOps team might know they typically spend 20% of time on support tickets (based on historical data).

- Multiple projects pipeline: If you’re planning capacity at a team or department level across projects, list all committed projects and their expected effort per month/quarter. Tools or historical data can help; if not, gather estimates from project owners.

- Seasonal peaks: Note if demand fluctuates (quarter-end reports always spike workload, or marketing campaigns before holidays require extra hours, etc.).

- Critical deadlines: Mark periods where demand absolutely must be met (like a product launch date). This helps prioritize resource allocation during those times.

- It might help to build a simple table: e.g., for each month, how many hours of each skill needed. Or use story points per sprint if in Agile. Regardless of format, quantify the demand as best as possible. It won’t be 100% precise (uncertainty is normal), but you can approximate. Often, demand is initially higher than capacity – that’s okay, that’s why we plan.

- Available Capacity (Headcount & Availability): Next, calculate your team’s capacity. Key elements:

- Team members and hours: List each team member (or role) and how many hours per week or month they normally can contribute. A full-time person might be 40 hours/week, but remember to adjust for productive time. If you assume 80% utilization, that’s 32 hours/week effective per person. You might directly assume ~32 hours as their capacity for project work weekly. Alternatively, some do 7 hours/day (leaving 1 hour for admin). Be mindful of part-timers or folks not 100% allocated to your team.

- Holidays, vacations, other commitments: Subtract out any time they won’t be available. E.g., subtract national holidays in that period, known vacation days someone has scheduled, or other project allocations. If a person is 50% on another project, only count 50% of their time in your capacity.

- Skills or role matching: Capacity often needs to be assessed by role. For instance, you might have 100 hours of design work demand and 1 designer on the team. If that designer has capacity of 80 hours in the timeframe, you’re short on design capacity even if development capacity is fine. So break capacity (and demand) down by relevant categories (could be role, team, or person).

- Ramp-up or ramp-down: If you plan to hire someone or a team member is leaving mid-period, adjust capacity accordingly. E.g., new hire joining in March won’t be available Jan-Feb, or might be ramping (maybe assume 50% capacity their first month due to onboarding).

- Overtime or contractors: Decide if you will consider overtime as capacity (not ideal as routine, but sometimes you plan some overtime during crunch). If using contractors, add their hours to capacity for the periods they’ll be on board.

- Buffer: Some teams explicitly include a “buffer” in capacity. For example, only plan 90% of theoretical capacity to leave a 10% buffer for sick days or emergencies. That’s essentially a way to enforce utilization <100%. Another approach is incorporate contingency in demand estimates. Either way, acknowledging uncertainty with a buffer is wise.

- Summing this up gives you something like: Team capacity this month = 5 people * 4 weeks * 32 hours/week each = 640 hours, minus vacation (say 40 hours) = 600 hours effective capacity, for instance. Do this for each key role group as well (like 400 hours of engineering, 80 hours of design, etc., depending who’s on the team).

- Utilization Targets or Policy: This is more of a planning parameter. Decide on your target utilization (if not already dictated by company). Many teams use around 80% as mentioned. So if someone says “I can probably effectively do 6 hours of project work per day long-term,” that’s 75% of an 8-hour day. Choose what makes sense given your context (if you’re doing pure project work maybe 80-85% is okay; if lots of random tasks come up, maybe cap at 70%). This ensures you don’t plan people at 100% and then wonder why it failed.

- It’s also good to plan some slack for continuous improvement or learning – high-performing companies often allocate a bit of capacity to training or process improvements. If your team does that, factor it (e.g., 10% time for innovation, then only 90% remains for planned tasks).

- If management pushes for higher utilization, show them data: e.g., at 95-100% utilization, queues and delays skyrocket (there’s a queuing theory that shows at ~80% utilization, wait times are manageable, at 100% even a slight extra load causes infinite wait). In other words, pushback that planning people to 100% is setting up failure because any small delay causes a domino effect.

- Tool or Method to Compare: You’ll need a way to compare demand vs capacity. It could be as simple as an Excel sheet or a chart. Some terms:

- Resource histogram or heatmap: a chart that shows each time period and whether capacity > demand or vice versa (could highlight red where demand exceeds capacity).

- Capacity profile: listing capacity and demand side by side by week or month.

- Our template does exactly that: you input planned work and team availability, and it will show utilization % and flags where over 100%.

- If using software, many project management tools (or specific resource management tools) can display a workload chart or resource utilization report. For instance, Playbook’s scheduling view can highlight if a person is allocated over their capacity (often by red shading if >100%). This is real-time capacity management.

- In any case, make sure you can see the comparison clearly. It might be by role: e.g., “Design: 120h demand vs 100h capacity = 20h short (120% utilized). Dev: 500h demand vs 600h capacity = okay (83% utilized). QA: 80h demand vs 60h capacity = 20h short (133%).” This tells you hiring or shifting needs.

- Scenario planning: Sometimes you’ll adjust demand if capacity is insufficient (like cut a feature). It’s useful to have a model where you can tweak and see the effect (e.g., if we drop project C, what happens? Or if we hire one more person, how does utilization change?). Good capacity planning involves reviewing such scenarios with stakeholders.

By gathering the above, you set the stage for analysis. It might sound like a lot, but often you can reuse data from existing project plans or time tracking. If historical data exists (e.g., velocity of a team, average support hours per week), use that to inform your forecasts. The quality of input data will influence how accurate your capacity plan is – but don’t let seeking perfect data stop you. Even rough estimates are better than none, and you can refine over time.

Step-by-Step Capacity Planning Process

Let’s outline a straightforward step-by-step approach to capacity planning. This can be done at the start of a project, during annual planning, or whenever you need to reassess (quarterly is common):

Step 1: List Upcoming Work (Demand Forecast)

Start by compiling everything the team is expected to work on in the given period. For a single project manager planning their project, this means list all project tasks or phases with effort estimates. If you’re a department manager planning for multiple projects, list all projects or major outputs. Include:

- Existing commitments: projects in flight, maintenance duties, support rotations, etc.

- New projects or initiatives: that are slated to start or continue in the period.

- Operational/administrative load: meetings, reporting, etc., if significant (some categorize this under an assumed utilization reduction instead).

For each item, estimate the effort required in the period. If your period is monthly, estimate how much will be done that month (e.g., Project A will need 200 hours of dev in Jan, 150 in Feb, etc.). If unsure, you may distribute evenly or use any known milestones to allocate effort. It might be easiest to estimate total effort then break it by month assuming linear progress or front-loaded, etc. Also consider priorities – note which work is must-do vs could slip (this helps in making trade-offs later).

Step 2: Determine Team Capacity

Identify all team members (or roles) available for that period and calculate their capacity. A simple way:

- Calculate weekly capacity per person = (Hours per week * utilization target). E.g., 40 * 0.8 = 32 hrs/week per person for project work.

- Multiply by number of weeks in your planning horizon (adjust if someone not available all weeks).

- Subtract any known time off or other allocations. E.g., John: 32h/wk * 4 wks = 128h, minus 16h vacation = 112h for month.

- Do this for each, or aggregate by role. Perhaps make a small table:

- Developer A: 112h (for January),

- Developer B: 128h,

- QA X: 80h, etc.

- Sum up to total capacity per role and overall. For instance, Dev team total capacity in Jan = 240h, QA = 80h, etc.

Ensure the timeframe for capacity matches demand timeframe (if demand is monthly, capacity should be monthly hours; if by week, do weekly).

Step 3: Compare Demand vs Capacity

Now put them side by side. For each role or person, and overall:

- Calculate utilization = demand / capacity * 100%.

- Identify where demand exceeds capacity (>100% utilization). These are overloads. Mark them clearly (like highlight in red or bold).

- Identify where capacity exceeds demand significantly (under-utilization). Those might be opportunities to take on more work or reassign resources.

- For example, you find in January: Developers demand 300h vs capacity 240h = 125% (overloaded by 60h). QA demand 60h vs capacity 80h = 75% (some slack). Overall team 360h vs 320h = 113% – overloaded in total.

- Sometimes one role shortage can bottleneck the schedule (like not enough QA means testing phase will slip, even if devs have slack). So focus on each category.

- If you find overall you’re okay but one skill is over, you either need to shift some tasks to others if possible (cross-skill training or help) or address that specifically (maybe hire a contractor QA, etc.).

- If everything is under 100%, you’re in good shape capacity-wise (maybe too good – check if you’re using team fully or can commit to more).

This step basically reveals the gap: “We’re X hours (or Y people) short of meeting all demand” or “We have some extra capacity to spare.” It’s like shining a flashlight on potential trouble spots before you get there.

Step 4: Address Gaps – Adjust Plan

This is the decision-making part. If you have overload (demand > capacity), you need to do something, because as is, you’d overload the team and likely miss dates. Typical options:

- Add capacity: Can you onboard additional resources? Options include hiring new staff (if long-term need), bringing in contractors/consultants for the peak, borrowing someone from another team, or increasing hours (overtime) temporarily. Each has cost and feasibility considerations. E.g., if dev is short, can we bring an external dev for 2 months? Capacity planning gives justification for these requests (you can show management “We’re at 125% – if you want the timeline, we need an extra developer for 4 weeks”).

- Reduce demand (scope): Can you drop or delay some work? Prioritize tasks/projects – maybe a lower priority project can be postponed to next quarter to free capacity. Or within a project, reduce scope/features to cut workload. If you can’t get more people, adjusting the workload is the safest way to avoid overage. For example, decide that Project Z will slip to next quarter, so remove those hours from this period’s demand.

- Extend timeline: If neither adding people nor cutting scope is an option, the last lever is time. Push deadlines out until demand fits capacity. This might mean negotiating with stakeholders to deliver in 6 weeks instead of 4, for instance. With a clear capacity rationale, that negotiation is more evidence-based. (Of course, extending timeline often has cost and satisfaction impacts, but missing a deadline due to burnout or quality issues is worse).

- Improve efficiency: A longer-term angle – are there productivity improvements to effectively increase capacity (automation, better tools)? This is usually not immediate, but worth noting if say a certain type of work is bottlenecking, maybe invest in training or tools.

- Redistribute work: If one role is over capacity and another under, can some tasks be reassigned or shared? E.g., maybe a developer can assist with some testing tasks if QA is overloaded (with training or oversight). Or a business analyst might help the UX researcher if they have similar skills. This depends on skill flex and is a temporary fix, but in small teams people often wear multiple hats.

Document your decisions. For instance, you might conclude: “We will hire 1 contractor in Feb-March to cover the extra 160 hours of work” and/or “We will defer Feature X to next release, reducing demand by 100 hours” and/or “We will allow overtime of 10 hours per person in the last 2 weeks if needed (last resort)”. Also, make sure to communicate this to relevant stakeholders – e.g., product owner about scope cut, or management about hiring need.

If you have underload (capacity > demand), that’s a good problem but still plan how to use that wisely. Perhaps you pull in some planned future work early, or give team time for innovation, or cross-train folks, etc. It’s an opportunity: maybe deliver faster, or rotate people to help others, or reduce cost by not using contractors fully if not needed. Just ensure people aren’t idle out of oversight.

Step 5: Reconcile with Schedule

Once adjustments are decided, update your project schedule or roadmap to reflect them. Capacity planning might lead to changing a deadline or removing tasks; those changes should be reflected in the timeline and communicated. Similarly, if adding resources, incorporate them into the plan and assign work accordingly (like adjust Gantt dependencies if needed).

This step is basically implementing the solution and making sure the project plan is now realistic. If you extended the timeline by 2 weeks, adjust all dependent tasks; if you cut scope, remove those tasks from the plan, etc.

Now your schedule is capacity-optimized – meaning if all goes roughly as planned, your team should be able to handle it without heroic efforts.

Step 6: Monitor & Update Continuously

Capacity planning isn’t one-and-done (unless it’s a very short project with stable scope). New work can emerge, people’s availability changes (surprise leave, someone falls sick, etc.), or estimates prove wrong (tasks take more effort than thought). So, it’s crucial to monitor actual vs planned:

- Track actual hours or progress and compare to the forecast. Are tasks taking more effort? Is someone overloaded already this week?

- Many teams hold a weekly review of workload, or in Agile, each sprint planning re-assesses capacity (who’s off next sprint? what’s our velocity? etc.).

- Use tools: a resource workload chart that updates as tasks complete or as people log hours. In Playbook, for example, if tasks slip, the tool can highlight that a certain person will now be overloaded next week unless adjustments are made (this is where AI Resource Scheduling can help automatically reschedule tasks within capacity constraints).

- If you detect variance, adjust early. If a project adds scope (new features) and thus demand increases, run a fresh capacity check to see if you need more adjustments (maybe that triggers an additional hire or pushing some features out).

- Also, update the team if capacity plans change – e.g., “We initially planned to bring a contractor but the hiring didn’t go through, so we’ll need to shift some work to next sprint” – transparency helps the team trust the process.

A quick example following these steps: Suppose a Software Dev Team planning next month. They list tasks (features to develop, bugs to fix) estimated at 500 hours of dev work and 100 hours of testing. They have 4 devs and 1 tester. Each dev ~ (160h 0.8) = 128h capacity, so 4 devs = 512h; tester = (1600.8) = 128h. At first glance, dev demand 500 vs 512 capacity – fits, 98% utilized (good). Tester demand 100 vs 128 capacity – fits, ~78% utilized (also good). However, maybe one dev is also splitting time with another project 50%. That reduces dev capacity by some. If after adjusting, dev capacity was say 400h, then 500 vs 400 = 125%. They’d spot 100h shortage for dev. They might decide to pull a developer from a less urgent project or have developers do some overtime or cut a low-priority feature. They adjust until demand ~ capacity. Then they monitor: if mid-month one feature is taking far longer (demand increasing), they’ll revisit, maybe deferring a lower priority bug fix to keep the important tasks doable.

This process might sound involved, but many of these steps can be done quickly once data is in place – especially with a template or software. It’s far less painful than the consequences of not doing it, which often involve last-minute scrambles, project delays, or team burnout.

Example: Simple Capacity Planning Model for a Software Team

Let’s illustrate with numbers to make it concrete. Consider a software development team working on two projects simultaneously. The team consists of:

- 5 Developers

- 2 QA/Testers

- 1 UX Designer

- 1 Project Manager (who also has some capacity for BA tasks, etc.)

We’ll plan for the next 1 month (4 weeks).

Step 1: Demand Forecast – The work for the month:

- Project Alpha: New feature development – estimated 300 hours of dev work, 80 hours of testing, 20 hours of design.

- Project Beta: Ongoing improvements – estimated 150 hours dev, 40 hours testing, 10 hours design.

- Support/Maintenance: expected ~50 hours dev for bug fixes from production issues (based on past averages), and ~10 hours QA.

- Meetings/Other (non-project overhead): Let’s estimate each person spends about 4 hours/week on meetings/admin (so 16 hours per person per month that is effectively “demand” not directed to project tasks).

Total demand by role:

- Dev demand = 300 + 150 + 50 + (meetings*5 devs). Wait, meeting time we count in capacity reduction usually, but we can count as demand too: 5 devs * 16h = 80h of dev time goes to meetings. However, often we wouldn’t allocate meeting time as separate “demand”; instead, we’d just reduce capacity. Let’s handle it by capacity reduction in the next step to avoid double counting.

So ignoring meetings for now:

Dev = 300 + 150 + 50 = 500 hours of actual dev tasks.

QA demand = 80 + 40 + 10 (assuming QA also handles some maintenance verification) = 130 hours.

Design (UX) demand = 20 + 10 = 30 hours.

PM/BA demand = maybe they will spend time coordinating – but we might consider PM overhead separate (if PM is 1 person, perhaps their whole job is PM, which is already accounted as them being at capacity).

Let’s say the PM needs to do 20 hours of requirements documentation or coordination this month specific to projects (we’ll call that demand on PM).

Step 2: Capacity – Now the team’s capacity:

- Work weeks in month: assume 4 weeks * 40 hours = 160 hours per full-time person if 100%.

- We decide target utilization ~80% for productive project work (the rest is overhead like meetings, general discussions, breaks).

- Thus per person effective capacity ~ 0.8 * 160 = 128 hours of actual working on tasks.

- Check time off: Suppose 1 dev has a planned vacation for 1 week (40h) during this month.

- Check other commitments: Are all 5 devs fully dedicated? Possibly one dev is also acting as a scrum master 10% time (but that might be under overhead). Let’s assume all devs on these projects except vacation.

- Devs: 5 devs * 128h = 640h base. Subtract one dev’s vacation 40h (but note the utilization 80% was on full time, do we subtract full 40h or 32h effective? Actually if one dev is out a week, their capacity is 128h - (0.840) because that week they'd have produced 32h if here. Let’s keep simpler: we’ll treat capacity as 4 devs at 128 + 1 dev at 128-32 [since one week off, leaving 3 weeks of work at 80% = 96h]. So capacity = 4128 + 96 = 512 + 96 = 608 hours dev capacity.)

- QA: 2 testers * 128h = 256 hours QA capacity (assuming no time off for them).

- Designer: 1 * 128h = 128 hours design capacity.

- PM: 1 * 128h = 128 hours PM capacity (though PM might not be utilized 80% on project tasks if they have management duties, but let’s go with it).

Now, we also have those meeting hours – where did they go? In reality, the 128h we computed is after leaving 20% slack which covers meetings and such. So we don’t explicitly subtract meetings further; it’s built in. If the team had unusually high overhead, we might reduce utilization or account separately. But 80% presumably covers typical overhead.

Step 3: Compare:

- Dev demand 500h vs dev capacity 608h. Utilization = 500/608 ≈ 82%. That’s actually fine. (It means dev team is used 82% of their max 80% allocation – basically ~65% of total time, leaving a bit of buffer. It also means maybe they have ~108 hours of slack beyond planned tasks. Could use for stretch goals or reduce if needed.)

- QA demand 130h vs QA capacity 256h. Utilization = 51%. That indicates QA has a lot of free capacity. That seems suspiciously low – did we overestimate QA capacity or under-plan testing? Possibly in practice, those testers might do other things or maybe our estimates are low. But with given numbers, testers are underutilized. They could either take on more testing (maybe we estimated too low), or help elsewhere (maybe help with test automation or assist dev, etc.). For now, it’s fine; better under than over. It suggests maybe we could handle more testing tasks (like extra quality improvements) if needed.

- Design demand 30h vs capacity 128h. Utilization = ~23%. Very low – the designer has light work this month. Perhaps they can be assigned to some other project or do research/improvements. Or maybe this is expected because heavy design was in earlier phases.

- PM demand ~20h vs capacity 128h = 16%. Also low, but PM might be spending remaining time on general management overhead not counted as “demand tasks”.

So, initial comparison shows no role is over capacity. The developers at 82% of effective capacity (which is roughly full because we gave them 20% buffer already, now they’d be using about 82% of that 80% – that is ~66% of total time, leaving some cushion). QA and UX are underutilized.

Given this, do we have a surplus capacity we could fill? Possibly. The devs are a bit high but manageable; testers are only half busy. Maybe this means either we can pull in some testing tasks that were not explicitly planned (like do more thorough testing or help automate tests). Or, if a tester has skills, maybe they help with documentation or something to increase their contribution. The UX being at 23% suggests maybe we can start next month’s design work early (designer could start designing features planned for the following month if known). So under-utilization sometimes means you can get ahead or allocate that person to another project temporarily.

But let’s modify scenario: what if we had one less developer? Then dev capacity would be 608 - 128 = 480h. Then dev demand 500h vs 480h = 104% – slight overload. That would highlight a need to adjust: either find that extra 20h capacity (overtime or borrow a dev from elsewhere for a few days) or drop something (maybe push a small feature).

Or say a new unplanned request came mid-month adding 100h dev work. Then demand becomes 600h vs 608 capacity = 99% (still okay). But if bigger, like 200h, then 700 vs 608 = 115% – that’s a problem. We’d then do step 4.

Step 4: Address Gaps – In our actual numbers, no gap to fix (we’re under 100%). If we had a gap, here’s what we might do:

- If dev was 125% utilized, we could say hire a contractor for a month (assuming cost is justified) to supply, say, 160h extra dev hours, bringing utilization down. Or if not, remove some dev tasks (maybe decide to postpone that maintenance or minor improvements).

- Since QA was under, maybe if dev was over, testers could help by picking up some minor coding tasks or test automation that devs would otherwise do – this uses QA’s spare capacity and alleviates dev. (This depends on skill and is not always possible, but agile teams sometimes have testers help with simpler coding or vice versa).

- In terms of timeline, if we had to, we could extend timeline. E.g., deliver Project Beta a few weeks later to reduce overlapping demand. In our case, capacity is fine.

Step 5: Implement Changes – If we decided something like hire contractor, we’d update the plan to include tasks assigned to contractor, or adjust the timeline if that was the route.

Step 6: Monitor – For instance, mid-month, we see Project Alpha tasks are taking longer. By week 2, 200h of dev work remains (which originally was planned to be maybe 150h by then). So we now foresee an extra 50h needed. We recalc quickly: dev initial demand 500 + 50 = 550 vs 608 cap = ~90% – still okay, but reduces our slack. QA might also go up if more testing needed. We keep an eye. If something threatens to go beyond capacity, we implement a backup plan (maybe ask devs to do a Saturday if short-term crunch, or drop a less crucial Beta improvement, etc.).

This example is simplified, but it shows how the numbers guide decisions:

- It highlighted that testers and designers have lots of free capacity – which might prompt the manager to either assign them to other work (maybe the designer can help product manager with user research or testers can improve test scripts).

- It confirmed developers are near a healthy limit but not over – important to ensure we can deliver features on time.

- It would clearly show if we had a resource gap – like if we only had 3 devs, capacity would be 384h, and with 500h demand that’s 130% – a glaring issue to fix by scope or staffing.

One could imagine presenting a simple chart:

|

Role |

Demand (hrs) |

Capacity (hrs) |

Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dev |

500 |

608 |

82% |

|

QA |

130 |

256 |

51% |

|

UX |

30 |

128 |

23% |

From that, one might decide, “It looks like our QA can handle more – maybe we allocate them to do more thorough testing or assist with documenting test cases, and our UX could start on next sprint's designs. Our devs are relatively well-loaded but have some buffer for unforeseen work, which is good. If any new work comes, we can absorb up to ~108 hours before hitting full capacity. So we’re in a safe zone.”

This exercise not only helps avoid overload but can also justify resource usage: If stakeholders see QA at 51%, they might ask “Why do we have so much QA idle time?” You might answer, “We planned very conservatively for testing (or QA also supports another project not listed, etc.). Perhaps we can reduce one tester or assign them elsewhere next month if this pattern continues.” Capacity planning thus informs resource allocation beyond just one project – it feeds into organizational resource management (e.g., deciding to move a person to a busier team if one is consistently underloaded).

Finally, note that capacity planning deals in estimates and forecasts. It won't ever be perfect – but it dramatically improves foresight. The more you do it, the better you get at estimating and adjusting. Also, as conditions change (and they will), treat the capacity plan as a living document. It’s much like navigating a ship – you set a course (plan), but you constantly check the wind and currents (project changes) and adjust as needed to still reach the destination (deadline) with the crew in good shape.

Monitor, Reforecast, and Adjust

Capacity planning is not a set-it-and-forget-it exercise. To ensure you actually hit your dates and avoid overload, you need to monitor actual progress against your plan and be ready to re-forecast capacity vs demand when things change. Here’s how to stay on top of it:

- Track Actuals vs Plan: If you have time tracking or project progress data, use it. For example, at the end of each week, check how many hours were spent vs what was planned. Are certain tasks burning more hours than expected? Is someone spending unexpected time on unplanned work? This can signal that your demand forecast was off. Modern project tools might show, for instance, a task was estimated 16h but took 24h – that extra 8h is going to consume capacity you had earmarked for something else. Identifying that early allows you to adjust upcoming plans.

- Team Feedback: Get input from the team regularly. They often know before the numbers show if they’re overwhelmed or underutilized. A developer might say in a stand-up, “I’m swamped, working late to finish Feature A” – that’s a red flag you might be at or beyond capacity in that area. Or a tester might say, “I’m twiddling my thumbs waiting for something to test” – meaning capacity is free that could perhaps help elsewhere.

- Adjust Task Assignments: A big part of capacity management is shuffling tasks around as needed. If mid-cycle you see one person overloaded and another light, consider reassigning some tasks (assuming skill match) or pairing them up. Tools often let you see individual loads; for example, a heatmap might show Alice at 120% and Bob at 60% – perhaps Bob can take something off Alice’s plate.

- Revisit Forecast for New Work: Projects rarely remain static. New requirements emerge, priorities shift, or additional projects get approved. Whenever new work is added (or significant scope change), go through a mini capacity planning again: add the demand, see if it fits. For instance, say mid-month, Project Beta gets an extra feature request of 50 dev hours and 20 QA hours. Immediately update your demand totals and see the new utilization. If that pushes dev to 95% and QA to 60%, maybe it’s still okay – but your safety margin shrank. If it pushes dev to 110%, you know you must negotiate something (maybe push that feature to next month or get extra help). Don’t just accept work without adjusting somewhere; capacity planning gives you the justification to push back or find more capacity.

- Regular Cadence for Capacity Review: Many teams do this monthly or quarterly formally, and weekly informally. For example, in Agile Scrum:

- Before each sprint (every 2 weeks, say), the team assesses who’s available and how much work can be pulled in (that’s capacity planning in practice).

- In Kanban, teams limit Work in Progress and monitor throughput which indirectly manages capacity.

- In a traditional project, you might formally re-forecast at phase gates or monthly project reviews: “We completed phase 1 but used 10% more dev hours than planned – if that trend continues, final phase might need adjustment or extra resources.”

- If your organization has a resource manager or PMO, they might facilitate a monthly resource planning meeting, where upcoming capacity for all teams is compared to project needs and they shuffle assignments or timelines accordingly.

- Use Tools & Automation: If possible, leverage software. Some resource management tools will automatically alert you if a person is scheduled beyond their capacity or if new tasks assigned exceed someone’s availability. Playbook’s AI scheduling can dynamically adjust tasks around resource constraints – essentially automating some capacity adjustments by delaying tasks until a resource is free, or suggesting who could take a task based on free capacity. Reports that show remaining capacity for a period can help PMs make quick calls about new requests (“No, we can’t take another project this month, we’re at 95% capacity already – how about next month when we drop to 70%?”).

- Communicate Early and Often: If you foresee a capacity issue that could affect delivery, raise it to stakeholders sooner rather than later. For example, “We’re tracking about 100 hours over capacity on development – at this rate, the release might slip by two weeks or require overtime. We have options: reduce scope or add temporary help. I recommend we [action].” This proactive communication builds trust and allows course correction while options are open. Surprising a client on the delivery date with “we couldn’t finish because we were too busy” is not a good look; far better to say a month in advance “we have a resource crunch; let’s adjust plan now.”

Reforecasting Frequency: A common question is, “How often should I redo the capacity plan?” The answer: as often as needed given volatility of your environment, but at least periodically.

- If your project is relatively stable and long, maybe monthly is fine.

- If you’re in a dynamic environment with changes weekly, you might do quick weekly updates.

- Some teams do a formal capacity plan at the start of each quarter, and then minor tweaks each month or sprint.

- Also re-forecast at major change events: if a key team member leaves (capacity drops), if new hires join (capacity rises), if a major new project is approved, or if priorities shuffle drastically (meaning demand volumes change).

In the earlier Software Team example, suppose after 2 weeks we see devs had to spend unexpected time on urgent bug fixes (say an extra 40h not originally planned). We update demand for “support” from 50h to 90h. Now dev demand is 540h vs 608h capacity (89% -> now ~89%). Still okay, but less slack. We also see QA demand was under because dev behind schedule – QA did only 50h of testing so far out of 65 planned. So QA might be underutilized. But if dev got behind, it might push more testing into the later weeks, which could increase peak QA demand later. We could reforecast QA for later weeks to be higher and see if their capacity can cover it (likely yes in our example because they had slack). If not, maybe devs help test in final week to meet deadline, etc. The point is, by reforecasting midstream, we can reorganize so that final delivery still happens smoothly (perhaps testers pick up some documentation tasks in early weeks and then are ready to blitz test in last week when dev finishes features).

Handling Common Issues:

- If someone falls sick for a few days – that’s lost capacity. If minor, the buffer might absorb it. If major (like a key person out for a month), you must re-do capacity plan without them and likely enact mitigation (reallocate work, delay tasks, get temp help).

- If multiple projects share people, coordinate capacity planning across them. Nothing worse than each project manager planning assuming they have 50% of someone, but combined they needed 120%. Having an overview (say a PMO keeps a master resource plan) prevents overallocation across projects. This is where a central tool can shine – showing a person’s total assignments across all projects vs their capacity. If you manage only one project, still be aware your team members might have other duties outside your project eating their capacity.

Burnout Check: Monitoring capacity isn’t just about numbers; watch morale and behavior. If people are constantly working late, complaining of burnout, or quality slipping, it’s a sign capacity is exceeded even if on paper it looked fine. Perhaps tasks were underestimated (a capacity planning input issue) or the utilization target was too aggressive (maybe 80% was too high given lots of context switching). Don’t hesitate to revise assumptions – maybe effectively your team can only give 70% to project work due to unforeseen overhead, so adjust future plans accordingly. It’s better to plan realistically and deliver, than plan optimistically and burn out or fail.

Celebrate Balance Achievements: It’s worth noting when capacity planning works well. For example, if a big crunch was avoided because you foresaw the need to bring in extra help, acknowledge that win. “We brought in two contractors in March and as a result, we hit our deadline without overworking the core team – that was a result of good capacity planning.” This reinforces the practice’s value to stakeholders (so they keep supporting it, especially when you request resources or changes based on it).

In conclusion, capacity planning is a continuous cycle: Plan → Execute → Check → Adjust (repeat). It aligns with the PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycle, which is fundamental to project control. When done regularly, it becomes second nature and not a burdensome task – just part of how you manage projects. And it pays off by giving you early warning of issues and the ability to confidently commit to dates knowing you have the resources to back it up.

Capacity Planning Best Practices

Before we wrap up, here are some battle-tested best practices and tips to get the most out of capacity planning:

- Aim for 70-80% Utilization Max: We’ve said it, but it bears repeating. Don’t plan people at 100%. Leave slack for the unexpected. One study noted teams with around 80% utilization optimize efficiency and accommodate variability. If you plan at 100% and something goes wrong (which it will), you have no buffer. Also, people are not robots – they need short breaks, time to think, training, etc. A healthy buffer range is typically 20-30%. If your work is highly repetitive and predictable, you might push towards 85-90%, but be cautious. It’s better to slightly under-commit and then use extra time for improvements or pulled-forward tasks, than to over-commit and miss deadlines.

- Include Non-Project Time: Don’t forget to factor in things like meetings, holidays, personal time off, company events, training sessions etc., as they reduce capacity. A common pitfall is to assume 8 hours a day of productive time. In reality, if someone has daily team meeting (0.5h), some emails (0.5h), one-on-ones, etc., they might only get ~6 real hours (or less) on project tasks. That’s why we do the utilization factor. If your company has frequent events or, say, half-day Fridays in summer, incorporate that. Or if it’s end-of-year and people have many holidays, don’t count those days.

- Use Historical Data: If you have timesheets or velocity data, use it to sanity-check your forecasts. E.g., if historically your team delivered ~100 story points per sprint, and now backlog suggests 150 in next sprint, is that realistic? Or if marketing projects of similar size took ~200 hours last time, don’t assume you can magically do this one in 100 without reason. Historical utilization reports can show that “we usually only achieve 70% utilization because of X meetings and Y support calls” – then plan accordingly. Past project post-mortems often highlight resource issues that you can avoid repeating by planning better.

- Prioritize and Build Contingency Plans: Always know what work is critical vs nice-to-have. Then, if capacity crunch hits, you can quickly trim the non-essentials. In your capacity plan, it can help to mark which tasks or projects would be first to go if something had to give. Similarly, have a “wish list” of tasks that could fill time if you end up with extra capacity (like improvement tasks, refactoring, backlog grooming, etc.). This way, you can maintain optimal use without idle time or overload – capacity planning is about balancing, and having flexible scope helps achieve that.

- Consider Different Scenarios: It can be useful to do a capacity stress test: e.g., “What if we lose one team member unexpectedly? Can we still deliver? How would we cope?” or “What if demand is 20% higher than anticipated (common in projects)? Where do we stand?” Running these scenarios can prompt risk mitigations (maybe cross-training team members to cover each other, or identifying a backup contractor to call if needed). Conversely, “what if demand is lower – do we have other work to utilize people so we’re not paying them to sit idle?” (maybe have an improvement project ready).

- Keep a High-Level Org View: Individual project capacity planning is great, but if you have multiple projects or departments, someone should look at the big picture to see if resources are optimally allocated. For instance, our example showed testers only 51% utilized; maybe another project’s testers are at 120%. An organization that has visibility can temporarily move one tester over or share resources to level things out. A capacity planning tool across projects can highlight these imbalances – sometimes called resource leveling across the portfolio.

- Involve Team Members in Planning: This improves accuracy and buy-in. Developers often know roughly how much they can do in a week. If your plan says 40h and they say “realistically I can only do about 30h of coding per week given meetings,” trust their input and plan for 30. Also, if they help create the plan, they’re more likely to commit to it (“we agreed this was doable”). And they will alert you sooner if something is off (“Remember we thought this task was 8h? It’s more like 20h – we’ll need to adjust”).

- Review Capacity before Accepting New Work: Whenever someone requests a new project or task insertion, get in the habit of checking your capacity plan first. It’s much easier to negotiate start dates or say no initially than to pull off a miracle later. You might respond to a request, “Looking at our team’s capacity, we can take that on in July once Project X is done, but not in June as we’re fully loaded.” If you present that with data (e.g., show the utilization chart for June at ~95%), it’s a rational discussion, not just a flat refusal. Often stakeholders will appreciate the transparency (or at least understand the constraint) – maybe they’ll provide more budget for resources if it’s urgent.

- Document Assumptions: When you do capacity planning, note assumptions like “No major production issues will occur,” “Client feedback cycle will be 1 week, not more,” or “Team will not be pulled to unplanned initiatives.” These are risks to capacity. By documenting them, you can later say “We planned assuming X; Y happened instead, so now we need to adjust.” It also helps you remember to adjust if you see those assumptions break down.

- Use Visuals to Communicate: Visual aids like Gantt charts with resource loading, burn-down charts, or simple bar charts of capacity vs demand help convey the message to both team and execs. For instance, a graph showing each week how many hours of work vs hours available quickly highlights peaks beyond capacity. Visualizing that “mountain” can be more persuasive than numbers buried in a spreadsheet. We provided a capacity planning calculator – you can use its output to create such visuals

- Connect to Schedule (Critical Path): Understand how capacity impacts your schedule’s critical path. For example, if a critical path task has more work than one person can handle in the time given, adding a second person (if possible) might shorten it or at least ensure it finishes on time. If capacity issues hit critical tasks, timeline slips. If they hit non-critical tasks, maybe not (or just use float). So focus resources on critical path if you can (Critical Path Method (CPM) ties into this – ensuring capacity for those tasks is paramount).

- Leverage Playbook’s Features: Since Playbook (assuming by context, an AI-driven PM tool) is mentioned, how can it help? Likely through:

- Auto-scheduling: It can automatically adjust task start/end based on resource availability (so tasks get pushed out if a person is booked, which visually shows you need to either accept later finish or add resource).

- What-if analysis: Some tools allow simulating adding a resource or moving a date and seeing effect on schedule instantly.

- Knowledge capture: Over time, Playbook might learn typical task durations and resource usage in your specific context (knowledge automation), thereby suggesting better estimates or flagging when you’re trying to do something historically problematic (like scheduling the same person on two heavy tasks simultaneously).

- Notifications: If someone’s tasks add up to > their capacity, it might notify the PM or that person to resolve the conflict.

- Using these advanced features can make capacity management more dynamic and less manual.

To sum up the best practices: plan conservatively, track diligently, adjust proactively, and communicate clearly. Capacity planning is both an art and a science – you forecast with data (science) and adjust with judgment (art) as projects unfold. But by following these principles, you significantly increase the chances of avoiding overload and delivering on time, while keeping your team healthy and productive.

FAQ

Conclusion

Capacity planning might not be the flashiest part of project management, but it is absolutely one of the most crucial for predictable, sustainable delivery. By systematically forecasting demand versus capacity, you turn the lights on in the room – suddenly you can see where the workload will likely overload the team, and you can act to prevent it. As we’ve explored, done right, capacity planning helps you hit your dates, avoid burnout, and make informed decisions about hiring, scheduling, and scoping.

Let’s recap the key points:

- Capacity planning is matching workload to resources. It’s a proactive step to ensure you’re not trying to pack 10 pounds of work into a 5 pound bag. This means taking into account how many people (and hours) you have and how much work is on their plate.

- We emphasized healthy utilization (70-80%) as a target. This buffer is the safety net that absorbs the day-to-day surprises and keeps the team sane. It’s far better to under-commit and over-deliver than the opposite.

- Step-by-step, we gather inputs (demand, capacity) and analyze gaps. The process isn’t rocket science – it’s about listing tasks, calculating available hours, and comparing. But the insights from that simple comparison are powerful. Many managers have “aha” moments like “No wonder we’re always running late, we consistently plan 2x the work our team can do.”

- We demonstrated with an example how capacity planning directly informed adjustments, such as adding a contractor or deferring a feature. Without that, a project might barrel forward until a crunch hits. With capacity planning, you tackle the issue at the planning table, not in the 11th hour.

- Continuous monitoring is vital. A plan is static, reality is dynamic. Regular check-ins and re-forecasting ensure your plan stays aligned with reality. If someone asks, “Can we take on this new task?” you now respond not just with gut feeling but with data: “We’re at 90% capacity this month; unless something else gives, we’d risk slipping another deliverable.”

- The benefits ripple beyond just meeting one deadline. Over time, good capacity planning leads to better project estimates, because you learn your team’s true throughput. It also fosters a culture of realistic commitments – team members trust that when a project is greenlit, it’s been thought through and they won’t be asked to perform miracles on a regular basis.

- From an organizational perspective, capacity planning builds credibility with stakeholders. Clients and executives prefer honest timelines and resource plans over optimistic promises that get broken. It might mean saying “no” or “not now” occasionally, but when you say “yes, we can do this by June 1,” they’ll know you mean it and have evidence to back it. Trust is earned in this way.

- There’s also a personal benefit for managers: less stress. Instead of constantly firefighting or pleading for help at the last minute, you have a handle on things. Of course, surprises will still happen – but you’ll catch many of them in advance. And when upper management asks “How did we end up in this crunch?”, you can show the thought process and where assumptions changed, making it a constructive conversation rather than an accusatory one.

- We also integrated how Playbook (the AI-powered PM software) can assist. Tools can automate the grunt work of capacity tracking and even suggest optimizations (that’s the “AI” part). But even if you’re just using a whiteboard or our provided spreadsheet, the thinking process is what counts.

In practice, when you implement capacity planning, you might encounter some pushback – perhaps someone says “We don’t have time for this planning stuff” or “Just get it done.” It’s here you can educate: a small investment in planning can save major time in execution. It’s like sharpening the axe before cutting the tree. Also, emphasize that capacity planning is not about doing less work; it’s about doing the work in a controlled, efficient way. It maximizes the chance of success for whatever goals are set.

Finally, capacity planning isn’t only about avoiding negatives (overload, burnout) – it’s also about enabling positives: innovation and continuous improvement. When your team isn’t running at 110%, they have the breathing room to think creatively, improve processes, and even build organizational knowledge (remember that Playbook’s selling point is “builds organizational intelligence” – likely by capturing knowledge when team members aren’t strictly firefighting). Some of the best improvements and risk mitigations come when teams have a little slack to reflect and refine. If you schedule everyone to the brim, those improvements never happen and you get stuck in a hamster wheel. But if capacity planning preserves some oxygen for the team, they will repay it with better work and ideas.

As we conclude, consider this analogy: Capacity planning is to project management what a flight plan is to a pilot. A pilot wouldn’t take off without calculating fuel, weight, weather conditions, and alternate routes. Similarly, as a project manager (or team lead), you shouldn’t launch into execution without checking the “fuel” (capacity) for the journey. It doesn’t guarantee smooth flying (there could be turbulence), but it means you won’t run out of fuel halfway or overload the plane. It means if turbulence hits, you have a plan to navigate around it.

So, embrace capacity planning as your project’s safety net and steering wheel. It will protect you from unrealistic demands, guide you in making tough decisions, and ultimately ensure that when you commit to deliver, you can do so with confidence. Your team will thank you – as their workload becomes more reasonable – and your stakeholders will thank you when projects consistently hit their targets.

Happy planning – may all your projects be well-resourced and your teams perfectly paced!