Gantt Chart vs. Timeline vs. Roadmap: When to Use Each

22 Oct 2025

Software Development

Introduction

Project managers often wonder which visualization is best: a Gantt chart, a timeline, or a roadmap? The answer depends on your audience and goal. Each of these tools serves a different purpose in planning and communicating a project. Gantt charts excel at detailed scheduling and dependency tracking, timelines provide an easy-to-digest chronological view, and roadmaps paint the big-picture strategy. In this guide, we’ll define each format, discuss pros and cons and show real-world examples of when to use each. By the end, you’ll know exactly whether to present your project as a Gantt chart, a timeline, or a roadmap – and how to leverage all three together for maximum clarity.

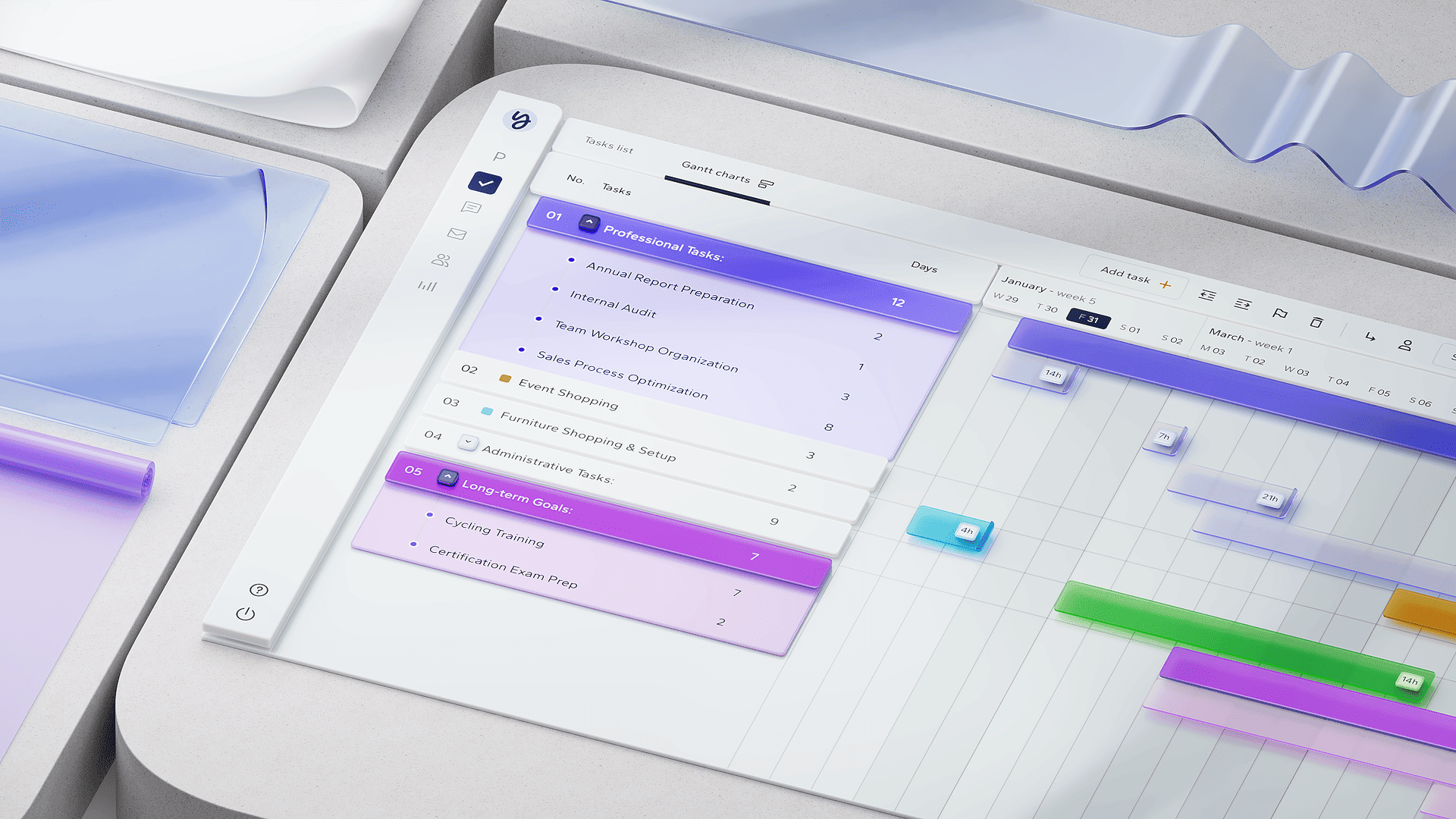

What Is a Gantt Chart?

A Gantt chart is a type of bar chart that illustrates a project schedule. Tasks are listed on the vertical axis, and time runs along the horizontal axis. Each task is represented by a horizontal bar spanning its start and end date. Critically, Gantt charts show task dependencies – relationships that indicate if one task must finish before another can start. Modern Gantt charts often highlight dependencies with lines or arrows between tasks and can display milestones and the project’s critical path. (The Critical Path Method (CPM): Fast, Visual Scheduling for Busy Teams – is commonly used alongside Gantts to identify the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines the minimum project duration.)

Origins: The Gantt chart has been around for over a century, first designed by Henry L. Gantt in the early 1910s. Despite its age, it remains one of the most widely used project management tools because it provides a comprehensive, visual timeline of the entire project.

Pros: Gantt charts are ideal for detailed planning and control. They force you to break the project into tasks, estimate durations, and define dependencies. This makes it easier to spot scheduling conflicts or overallocation early. Gantts also help track progress – you can compare planned vs. actual timelines and see which tasks are ahead or behind. For complex projects with many moving parts (software releases, construction builds, etc.), a Gantt offers a single source of truth for who needs to do what by when, and how delays impact the overall schedule. They are especially powerful when combined with resource management; for instance, linking your Gantt to Capacity Planning: Forecast Demand, Avoid Overload, and Hit Dates ensures you’re not scheduling tasks past your team’s actual capacity.

Cons: However, Gantt charts can become intimidating or unwieldy for certain audiences. An executive or client may find a large Gantt chart (with hundreds of tasks and dependency lines) overwhelming or too “in the weeds.” Updating a complex Gantt by hand can be time-consuming if plans change frequently. Additionally, Gantts assume a relatively linear progression of work – which is why traditional Gantt planning is often considered a waterfall approach. Agile teams working in short iterations might find a constantly changing Gantt less useful day-to-day. In short, Gantt charts are fantastic for project execution and tracking, but not always the best for high-level communication or fast-changing environments.

What Is a Project Timeline?

In project management, a timeline is a simple linear visualization of key events or milestones in chronological order. Unlike a Gantt chart, a basic timeline typically does not show every task or dependency – instead, it highlights the critical dates and deliverables. Think of a timeline as an “at-a-glance” schedule. For example, a marketing team might create a timeline of a campaign: Kickoff on Jan 5, Content complete by Feb 1, Launch on Mar 1. Each item is plotted along a horizontal time axis, but without detailed task bars or resource assignments.

Pros: Timelines are valued for their clarity and simplicity. They provide a high-level overview that anyone can understand in seconds. This makes them perfect for presenting to stakeholders who only care about major milestones or overall progress – e.g. client check-ins, executive briefings, or company-wide updates. A timeline helps set expectations (“We expect to reach Phase 1 completion by Q2”) without bogging the audience down in details. According to project management experts, timelines are especially useful for highlighting critical events such as project kickoffs, review meetings, and final deliverables. Because timelines omit granular detail, they tend to be cleaner and more visually appealing for storytelling. They answer “What’s happening when?” at a broad level.

Cons: The trade-off for simplicity is lack of detail. Timelines usually don’t show task dependencies, critical path, or resource workload. You can’t tell from a simple timeline which tasks might be at risk if one slips, or who is responsible for each item. There’s also no concept of percentage complete – a timeline won’t show how far along a milestone really is. For these reasons, a timeline does not replace a Gantt chart for internal team planning. It’s a communication tool more than an execution tool. If you rely only on a timeline, you risk missing lower-level scheduling conflicts or not conveying the full complexity of the work. In practice, many teams maintain a detailed plan (often a Gantt or task board) and then derive a timeline view for reporting upward or outward. Modern project software – including Playbook – often lets you toggle between a Gantt and a timeline using the same underlying data, so you can get both detailed and simplified views as needed. (In Playbook, for example, the AI Resource Scheduling can auto-generate a timeline for stakeholders while maintaining a detailed Gantt for the team, ensuring consistency.)

What Is a Roadmap?

A roadmap is a high-level strategic plan that outlines major phases, initiatives, or goals over time. Roadmaps are commonly used for product development, program planning, or business strategy. Unlike project timelines (which focus on when things happen) or Gantt charts (how to execute tasks), a roadmap emphasizes why and what. It connects the project’s deliverables to the organization’s larger objectives. Key elements of a roadmap typically include broad time frames (e.g. Q1, Q2, or “Now/Next/Later”), high-level themes or epics, and major milestones or releases. Importantly, a roadmap usually does not show task dependencies or granular tasks. It’s more about communicating direction and priorities at the executive level.

Pros: Roadmaps are excellent for strategic communication. They distill a complex initiative into an easily graspable plan focused on outcomes. For example, a product roadmap might show three upcoming release phases for the year, each tied to a strategic theme (“Improve User Retention” in Q1, “Expand to New Markets” in Q2, etc.). This ties day-to-day work back to the “big picture.” A roadmap helps secure buy-in from leadership and keeps teams aligned with organizational goals. It’s the preferred view for executives, board members, or clients who are more interested in overall progress and vision than the nitty-gritty. As ProductPlan explains, “A company can use a roadmap and a Gantt chart for the same initiative. The roadmap defines the why behind the project. The Gantt chart establishes how and when.”. In other words, the roadmap is about purpose and sequencing at a high level, while the Gantt charts the execution details. Roadmaps are also flexible; because they avoid exact dates in favor of broad timeframes, they accommodate change more easily. This makes them suitable for long-range planning where exact schedules are likely to shift.

Cons: The strength of a roadmap’s high-level focus is also its weakness for day-to-day management. Roadmaps lack detail – they won’t tell you who is responsible for each task or how two tasks might conflict. You generally can’t manage a project solely from a roadmap; it must be supported by more detailed plans (like Gantts or task boards) beneath it. Also, showing dependencies on a roadmap is challenging. By design, roadmaps abstract away dependencies to avoid complexity. If stakeholders ask, “Does Initiative B depend on A being finished?” the roadmap alone might not make it clear. One way to handle this is to annotate roadmaps with key dependency notes or use swimlanes for parallel workstreams. But if you need to see a detailed network of dependencies, a roadmap isn’t the right tool – a Gantt or a dependency matrix is better. Another potential con: roadmaps can become too high-level if not linked to execution. There’s a risk that a roadmap looks great but teams executing the work aren’t following it because it’s not integrated with their actual schedules. Tools like Playbook help mitigate this by linking the roadmap to real project data (thanks to 🔗 Knowledge Automation, each item on the roadmap can drill down into detailed tasks and documentation). In summary, roadmaps are not for micromanaging tasks; they are for inspiring and aligning around a common direction.

When to Use Each Format

Choosing between a Gantt chart, timeline, or roadmap comes down to who needs the information and what you need to convey. Below are general guidelines on when to use each, and when not to:

- Use a Gantt Chart when… you need to manage and track execution. Gantts shine for project teams and operations. If your audience is the internal project team, contractors, or anyone driving the work daily, a Gantt provides the detail they need. Use it for complex projects where task order, dependencies, and resource assignments matter – e.g. a construction project schedule, a software development sprint plan with interdependent tasks, or coordinating multiple teams on a product launch. Gantt charts are also vital for deadline-driven work: if missing one task’s date will slip others, the Gantt makes that visible. Essentially, when you have to answer “Can we still hit our date if Task X is two days late?” or “Who is doing what next week?”, the Gantt is the tool.

Avoid or supplement if you’re communicating to executives or clients who don’t need that level of detail – they might get lost in it. In those cases, create a simplified view (timeline or roadmap) in addition to the Gantt. - Use a Timeline when… you need to present a project overview clearly to stakeholders who are not involved in the daily grind. Timelines are perfect for status updates, project proposals, or any situation where you want to quickly show the sequence of key events. For example, an agency might show a new client a timeline of their marketing campaign, or a project manager might include a timeline slide in a quarterly review meeting. If your goal is to simplify and focus on major milestones (kickoff, phase completions, launch date) without technical details, choose a timeline. Timelines are also handy for internal communications in large organizations – a department head could outline all major projects on a single timeline to see overlaps and avoid scheduling conflicts for big events.

Avoid using only a timeline if the project is very complex or if team members need to self-manage their tasks. A timeline shouldn’t replace your internal task plan. If you find yourself manually adding lots of sub-items or notes to a timeline, that’s a sign you actually need a Gantt or detailed plan behind it. Also, if task dependencies or resource allocations are critical (e.g. in an engineering project), a simple timeline will be insufficient – pair it with a Gantt.

Use a Roadmap when… you need to communicate strategy and high-level plans, especially to senior leadership, investors, or cross-functional stakeholders. Roadmaps are ideal at the start of an initiative (to outline vision and phases) and for long-term planning beyond the current project. For instance, product managers use roadmaps to share how a product will evolve over the next 12-18 months. Portfolio managers use them to coordinate multiple projects under strategic themes. Choose a roadmap to answer questions like “What are our priorities this year?” or “How do these projects tie to our strategic objectives?” It’s the best format for storytelling – conveying the “why” and the context. A roadmap is also useful when you deliberately don’t want to commit to exact dates but need to show sequencing (e.g., a startup might show a roadmap to investors with broad timing like “Beta release in Q3” without day-level precision).

Avoid roadmaps for tracking day-to-day progress. If a stakeholder wants to see exactly which tasks are done or not, the roadmap won’t show it. Also, if your audience is the project delivery team, they will need more than the roadmap to execute – ensure the roadmap is backed by a detailed project plan. Roadmaps should be living documents that evolve with strategy; if you find you’re updating a roadmap weekly with detailed changes, that’s a sign to keep the roadmap high-level and manage details in a Gantt or other tool instead. In summary, use roadmaps for vision and alignment, not for scheduling or workload management.

Real-World Example: Combining Gantt, Timeline, and Roadmap

To demonstrate how these views complement each other, let’s walk through a scenario:

Example Project: Launching a New Product Feature (e.g., a mobile app feature release).

- Roadmap View (Strategic): The product manager creates a product roadmap for the next two quarters. It shows the feature launch as part of a strategic theme “Improve User Engagement Q1–Q2”. The roadmap highlights three broad phases: Design, Development, Beta Launch, with an ultimate Release milestone. It ties the feature to a larger goal (e.g. “Increase retention by 15%”). This roadmap is shown to executives and the sales team so they understand why this feature matters and roughly when it’s coming. The roadmap doesn’t list every sub-feature or task; it just communicates that by end of Q2, this new feature should be delivered, aligning with company strategy. Dependencies aren’t explicitly shown, but it’s clear that Beta comes before full Release, etc. The roadmap helps secure leadership buy-in and coordinates high-level timing with marketing and sales (so they can prepare launch materials in Q2).

- Timeline View (Tactical Overview): As the project enters execution, the project manager also prepares a timeline to share with the broader team and external stakeholders (like a client or other departments). This timeline includes key dates: UX design complete by Feb 15, Development sprints from Mar 1–Apr 30, Beta launch on May 1, Final launch by Jun 15. It might show a few extra milestones like “Security review” or “User testing sessions” if those are significant checkpoints. The timeline provides a clear picture of the project’s schedule without going into detail of every daily task. When a department head asks “What’s the plan for that feature rollout?”, the PM can show this timeline to convey the schedule in a straightforward way. It’s also used in team meetings to remind everyone of major deadlines. If a date slips, the timeline is updated accordingly to communicate the change downstream.

- Gantt Chart View (Execution Control): Behind the scenes, the development team and project manager maintain a detailed Gantt chart (likely in Playbook or another PM tool). The Gantt lists all tasks: design tasks (wireframing, prototype review), development tasks (APIs, UI coding, integration testing, etc.), QA testing, bug fixes, deployment steps. Each task has an owner (using a 🔗 RACI matrix can be helpful to assign clear responsibility for each task), a start and end date, and dependencies (e.g., “Back-end API development must finish before integration testing can start”). The Gantt chart allows the team to coordinate work daily and weekly. If one task is delayed, the PM immediately sees which subsequent tasks are affected (thanks to the dependency lines). They can then decide, for example, to shorten a later task or add resources to catch up – or if the delay is major, this will reflect on the timeline and roadmap (e.g., the Beta launch might slip a week, which would be communicated upward). Throughout execution, team members update the Gantt with progress (% complete), and the chart provides a real-time view of whether the project is on track to hit the key dates shown in the timeline and roadmap.

In this example, all three views work together. The roadmap set the vision and high-level timing, the timeline communicated the plan to a broad audience in an accessible way, and the Gantt chart was the working document to actually drive the project day-to-day. On launch day, an executive might look at the roadmap and celebrate that the company delivered on a promised initiative. Meanwhile, the project team knows it was the detailed Gantt planning and tracking (along with good capacity management and teamwork) that ensured that success. The takeaway: you don’t necessarily choose only one format – you often use each at different stages or for different stakeholders. A robust project management practice will layer these tools: strategic roadmap → summary timeline → detailed Gantt, each mapping to the same reality. Playbook, for instance, enables this multi-layered approach by letting you derive timelines and roadmaps from your Gantt data, so all views stay in sync (no manual rework).

Setting Up These Views in Your Tool

How you create a Gantt chart, timeline, or roadmap will depend on the tools you use. Here are some general steps and tips, including how Playbook simplifies the process:

- Creating a Gantt Chart: If making one manually, start by listing all your tasks in a spreadsheet or project tool. Include start and end dates (or durations), and define dependencies (Task B starts after Task A finishes, etc.). Then use a Gantt chart tool or Excel’s bar chart features to plot these on a timeline. Ensure you add key milestones (significant points in time, like “Project kickoff” or “Launch date”) – usually depicted with a diamond or star symbol on the Gantt. Many project management software solutions can generate a Gantt automatically once you input task info. In Playbook, for example, you can enter tasks (or import them) and the software’s AI Resource Scheduling will not only place them on the timeline but also adjust for resource availability, meaning the Gantt always stays feasible. A crucial part of setting up your Gantt is assigning resources and observing the resource load – if someone is assigned to overlapping tasks, the chart should highlight overallocation. Use color-coding or labels in your Gantt to show which team or person is responsible for each task (this is where linking your Gantt to a RACI chart can help; e.g., initials of the Accountable person next to each task bar). Once set up, review the Gantt with your team to verify sequencing and deadlines, and confirm that everyone knows their responsibilities.

- Creating a Timeline: To create a timeline, first identify the key milestones or phases of your project. These should be the events you would mention in a status meeting or report – for instance, “Design completed,” “Phase 1 Go-Live,” “Client approval received,” etc. Limit the number of items to avoid clutter (a timeline is most effective with perhaps 5–15 points, not every single task). Plot these points chronologically on a horizontal line. You can do this in presentation software or using a dedicated timeline maker. Add labels and, if helpful, brief descriptions. Make sure to indicate the time scale (are these dates, weeks, or months?). A best practice is to include today’s date or a progress indicator (“We are here”) on the timeline, so viewers can orient where the project currently stands. In Playbook, because your tasks and dates are already in the system, you can switch to a timeline view that automatically picks up milestones (for example, any task marked as a milestone in the Gantt can appear on the timeline view). This saves effort and ensures consistency. Pro tip: if your timeline is for an external audience, consider adding a one-line context for each item (e.g., “Beta Launch – release to 100 pilot users to gather feedback”). This ties the milestone back to purpose, which is something a roadmap also emphasizes.

- Creating a Roadmap: Begin by determining the time horizon and breakdown for your roadmap. Common formats are by quarter (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) or by month if it’s a shorter-term roadmap. Next, identify the major workstreams or categories relevant to your project or product. These become the swimlanes or sections of the roadmap. For example, if launching a product, lanes could be “Product Development,” “Infrastructure,” “Marketing,” “Customer Support Prep” – each representing a facet of the launch where work happens. Under each lane, list the big initiatives or deliverables. Plot each initiative as a bar spanning the expected timeframe. Since roadmaps are high-level, these bars might cover a range (e.g., a bar showing “Feature Development Phase” stretching from January to March). Use different colors or shapes to denote types of work or priority if needed (perhaps blue bars for development, green for marketing efforts, etc.). It’s often useful to include a legend or annotations for any key milestones on the roadmap (like a star or flag on the “Launch” date). One challenge is showing dependency or sequence – you can number initiatives or add arrows if it helps, but clarity is king: don’t clutter the roadmap. The goal is anyone looking at it can grasp the plan in under a minute. If executives want details, they can ask or refer to supporting docs. In Playbook, an interactive roadmap can be generated from your project portfolio data; by leveraging 🔗 Knowledge Automation, each roadmap item can link to documentation or specs, building organizational intelligence (for example, clicking a roadmap item might open the spec doc or risk register related to that initiative). Finally, review the roadmap with stakeholders to ensure it tells the right story – it should convey confidence and direction, without over-promising specifics.

Setting up each view initially takes some effort, but once done, maintain them. Keep the Gantt chart updated as the source of truth. From that, you can update timelines and roadmaps at major checkpoints (or automatically if using an integrated tool). This multi-view approach means at any time you can answer different questions: the team asks “What’s next on the schedule?” – show the Gantt; an executive asks “Are we on track for Q3 goals?” – show the roadmap; a client asks “When will feature X be delivered?” – show the timeline.

FAQ

Conclusion

In summary, Gantt charts, timelines, and roadmaps are complementary tools in a project manager’s toolkit. A Gantt chart is your go-to for controlling the details – it’s like the project’s engine room, where you can see every gear turning and how they mesh together. A timeline is the storytelling view, simplifying that complexity into a clear narrative of progress that anyone can grasp. A roadmap elevates the view further, connecting the project to strategic objectives and long-term vision. Picking the right one comes down to audience and purpose: use Gantt when precision and dependency management matter, timeline when communication and overview are key, and roadmap when focusing on strategy and big-picture alignment. Many successful projects will use all three at different times. By mastering each, you ensure you’re speaking the right language to the right people – whether it’s a developer asking “What’s next this week?” (show the Gantt), a client asking “When will we see results?” (show a timeline), or a CEO asking “How does this project support our goals?” (show the roadmap). Together, these formats create a layered communication system that keeps everyone from team members to executives on the same page, without either overwhelming detail or missing the forest for the trees.

Finally, remember that tools like Playbook can eliminate much of the manual effort – automatically generating these views and keeping them in sync. That means you spend less time fiddling with charts and more time delivering results. With the right visualization for the right audience, you’ll improve understanding, buy-in, and confidence in your project plan. Happy scheduling!